Exploring the Power of Autobiography and Biography by Calypso Morgan

I was reading The Silent Woman (1993) by Janet Malcolm, a book on the life of Sylvia Plath. What I thought to be a simple biography of the poet turned out to be more than that. The book was about the people who wrote about and profited from the now-deceased Sylvia Plath. The main way they did this was by writing about her life and her suicide.

Reading the book made me realise the power that biography and, in the same vein, autobiography hold in the publishing world through the reader’s perspective. This genre has been present for centuries and in different places: in the 5th century BC, the poet Ion of Chios wrote snippets of the lives of Pericles and Sophocles. In the 2nd century BC, Sima Qian, a classical historian, wrote a short account of himself in the Shiji (The Historical Records). These two early examples show both the longevity of the genre and the differences between the two forms. They also demonstrate how biography and autobiography have evolved into their current forms. The narrative would not be the same if one or the other were published.

However, in our day and age, nearly everybody on the planet has access to a form of social media and can talk, post, or write about themselves. On Goodreads, you can find the list of memoirs published in 2024, and the number is dizzying: 413 books with the tag “biography.” Why is there a need today to publish a book about oneself?

The first basic instinct is history. Our common past is built on physical archives as well as storytelling. Two individuals who lived at the same time would not have experienced the same thing. The format of the book becomes a way to preserve every statement. When Chileng Pa wrote Escaping the Khmer Rouge: A Cambodian

Memoir (2017), the first layer of the book is about his life hiding, running away, and fighting a dictatorship, but on a larger scale, it is about the history of an entire population. The main focus is the moment that would turn everything upside down for the rest of his existence. This kind of biography holds the voices of people who could not find the words to explain what happened to them. These testimonies have another goal: to shed light on events that the outside world often does not grasp or, in some cases, did not even know had taken place.

So, if memoirs can be used to expose stories that are normally forced to be forgotten, what about celebrities? Their purposes are not the same. More precisely, their objective is to reveal the darker and more gruesome parts we do not see under the spotlight of a celebrity’s life. When Jennette McCurdy released her bombshell I’m Glad My Mom Died (2022), an autobiography of her childhood star years, she detailed the abuse she experienced from her mother and the self-destructive patterns that followed. By writing, the author takes back control of the narrative of her life. The release of a book is symbolic of the message:

“I have survived, and I was silenced for too long. But now, listen to my story.”

These words are important in today’s society, where victims are still battling the blame that people try to impose on them through mass media and social media. Or where the justice system is not as impartial as it wishes to appear, and the balance often favours the predators. In a certain way, the autobiography is a shield against all the attacks that can be launched at them. The book is a physical form of the oral nature of the events. It is there and it will not change.

On the other hand, the simpler celebrities’ autobiographies recount their first memories, their first steps in the spotlight, their first flop, their first success, and finally the life they are living now. The memoir symbolises the entrance of the public figure into the history of society as a major figure in their respective field. A few examples I can give are Dave Grohl’s The Storyteller: Tales of Life and Music (2021), which anchors his name in punk, grunge and rock music with the bands Nirvana and Foo Fighters. Another example is Viola Davis’s Finding Me: A Memoir (2022), which serves to solidify her remarkable acting career and affirm that she was a figure deeply rooted in the Hollywood scene. She was her own person rather than being the “Black Meryl Streep.”

I have only quoted artists’ memoirs, but the same applies to politicians, especially in their case where they have a political agenda behind the scenes and also wish to be remembered for more than just their human side. They aim to show their closeness to the people to justify their policies during their careers.

The principle of presenting themselves as both figures in the public sphere and real people can also be applied to the memoirs of Internet content creators. We all remember 2015 when every YouTuber seemed to release a memoir at the peak of their popularity, such as Tyler Oakley’s Binge (2015) or Connor Franta’s A Work in Progress (2015), to name just a couple from that year. At first glance, this may appear to be a quick cash grab by the publishing industry. An Internet celebrity with a million fans is someone ready to buy anything from their favourite YouTuber. In some

cases, this is probably true, but I believe it is more than that. In every video promoting their book, a sentence or one of its many variations can be heard:

“A version of myself or a part of my life I was not ready to share with you until I wrote this book.”

For content creators and influencers, \”me\” is the most important element of their work. It is the defining feature of their persona. Their online identity and relatability are what attract a mass of fans, sometimes young and impressionable. When they write their autobiographies, the image projected online becomes what readers assume to be the offline reality. Given that the status of Internet celebrity is as ephemeral as the ever-changing landscape of social media, the physicality of the book serves the same purpose as it does for mainstream public figures. It secures their place in history, in this case, the history of the Internet. In some ways, they became the foundation of today’s influencer culture.

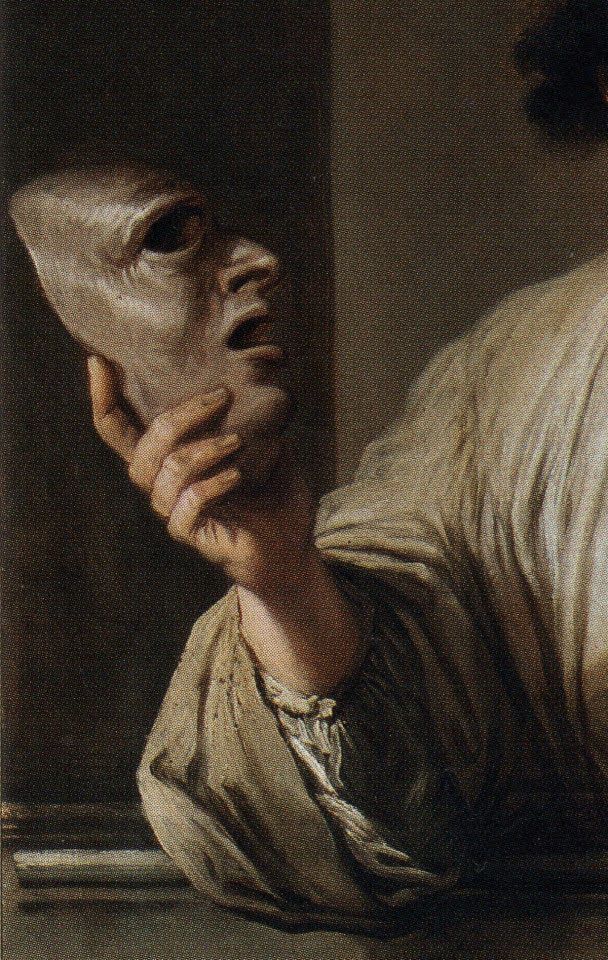

So then, what about biographies? If the autobiography has this layer of wanting to be a pillar in its sphere, the biography makes it more imposing. By simply having the subject of the book not as the author but as a third party, an outsider to the subject, it creates another dimension of exposing the life of the chosen subject. Janet Malcolm uses the expression \”keyhole\” when the writer and the readers want to know more as if they were spies or nosy neighbours. The biographer transforms themselves into a journalist or, even more, a private detective collecting evidence, conducting interviews with close ones, searching through archives, building a timeline, and so on. The author-detective puts on the mask of the impartial writer or tries to do so. By

publishing years of research, they can somehow elevate the simple status in the landscape to an idealised state, to the point of creating a sacred image.

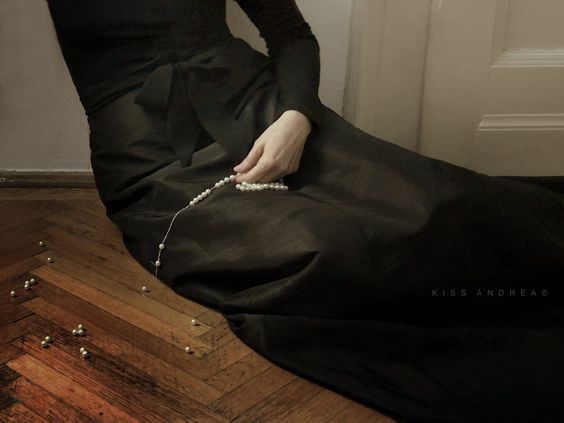

I am going to take the example of the artist who sparked this thought in writing: Sylvia Plath. A dozen biographies have been published since her death, adding to her short literary legacy. Plath became the symbol of the tortured artist woman, not understood by her peers at the time and struggling with mental health problems. She became the romantic figure in many groups, including one of the first embodiments of the “sad girl” aesthetic that was raging on Tumblr at one point.

If autobiographies and biographies have so much success, it is because of the silent contract signed between the writer and the reader. The author has to recount only the truth, but it is up to the reader, who is not obligated to accept it. However, if the genre has such great success, even when some works have questionable writing and retelling quality, the only reason is that the public is curious and has the desire to know more. It creates a false pretence of a deeper parasocial relationship.

This small essay will not do justice to some great books or, in reverse, make them seem to be amazing memoirs. But I wanted to present an interpretation of the behind-the-scenes of this genre that we often overlook.

About the Author

Calypso graduated with a Master\’s in art and media from the University of Paris 8. Her work focuses on the relationship between the Internet and art.